Second Skin | A More Sustainable Summer

10 MIN READ | Magazine | A.M.

Friday night. You’ve scheduled a much-needed night out involving activities somewhere between delightfully-tipsy and blackout-drunk, which, if all goes to plan, will be the first time you’ve seen the outside of your apartment in at least a week. You’ve been working on that presentation that’s due Monday, all the while convincing yourself that procrastination is good for art—and if your heart-rate is any indication, it most certainly isn’t. The clock’s ticking. Your friends call, disastrously breaking your never-call-when-you-can-text rule. As you stare at your laptop screen, the flashing cursor’s disappearing-reappearing act pulsates with an oppressive reminder that your deadline is fixed and your whole career now perilously pirouettes upon the outcome of a single word that sounds more foreign to you now than an alien dialect from some distant galaxy. Is it DÉC-olletage? Or dé-COLL-etage? You’ve now said this word aloud so many times it’s lost all meaning. Who invents them anyway? What did people do before audible language? Would it really be so bad if you were to cut ties with modern civilization and farm potatoes for a living?

Just me, I see.

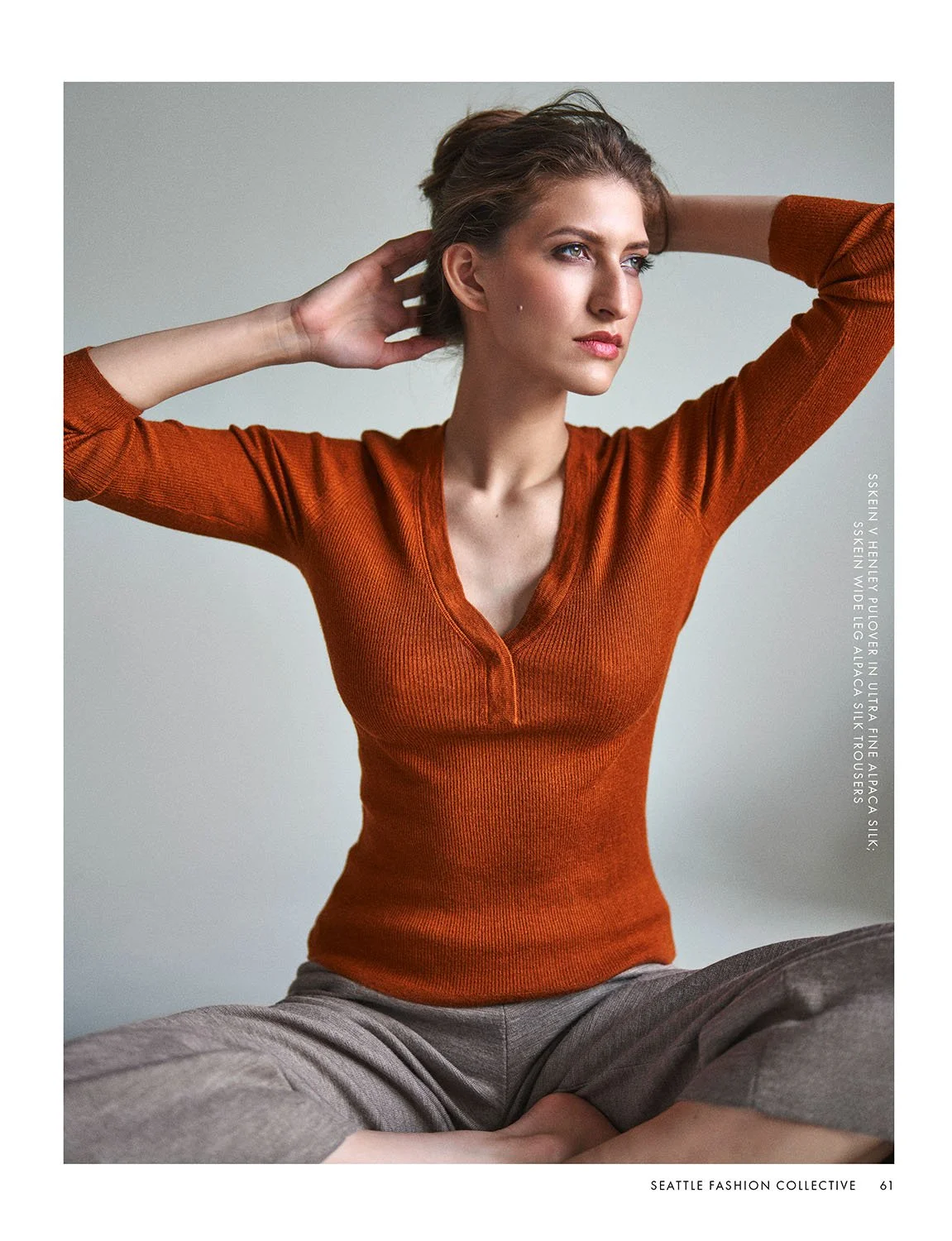

Sskein v Henley Pullover in Ultra Fine Alpaca Silk and Wide Leg Alpaca Silk Trousers.

THE NEW BABEL

Every-so-often we find new marketing words that have entered the contemporary lexicon forever altering their initial meaning. This wouldn’t be so bad. After all, language is fluid, shifting wildly across countless cultures and millennia. At its most reductive, words are merely sounds we create as we combine vowels and consonants. But they are so much more than that, carrying with them an explicit and implicit meaning that, at best, can reshape our world by allowing us to enter one another’s minds in order to understand the fundamental concepts within. We share with one another parts of ourselves that are only understood by our inmost beings. We use words to enrich our lives and give instruction to future generations. And words possess a power sharper than a double-edged sword which can in one breath heal, and in another, condemn.

As with the case of Roe v. Wade, the devil is in the details, and what was once meant to be a clear linguistic distinction intended to guide civilization into a more equal future, has now been rendered anachronistic and regrettably inert. All because of how we interpret words spoken not that long ago. In modern society, one has to first ask the question, What is meant by these words we use everyday? Do their meanings represent the understanding of the greater population? Do these words represent me? If not, then what?

In fashion, words like green and eco-friendly and sustainable have evolved to meet the marketing demands of our current direct-to-consumer economy. And not without good reason. The Rana Plaza factory collapse in Dhaka, Bangladesh was one of the most tragic and visible signs of fast-fashion’s eroding effects on consumer ethics and buying behavior. It was easy not to care where your garment was made—or under what conditions—when everyone from Macy’s to Zara fed you beautiful campaign images of happy and wealthy Americans buying more with less. But as with so many truths, what is seen can never be unseen. What’s left, then, in the wreckage of our lost innocence, stands as a rallying cry desperately pleading with us to do better.

And so, with the best of intensions, like a multi-headed hydra, our industry collectively chose to do just that. Innovations from across the planet added efficiencies throughout our global supply chains, promising that garment waste and carbon footprints were design flaws that would soon be designed out of the equation. And today, in some very meaningful ways, that promise seems to rings true. Large-scale corporations have invested heavily in recycling textiles, increasing efficiencies through automation, and reducing their carbon footprints where possible. But perhaps more impressively, small-scale businesses have revived many centuries-old artisan practices that have stood the test of time, contributing to a fundamental reimagining of the fashion-industrial-complex.

Paychi Guh Cashmere Printed Cardigan.

BEYOND GOOD AND EVIL

When you buy a garment from Zara and it tears two months later, then what? Will Zara accept your return? Will they repair the damage? Are there recycling drop-offs in your area that will reclaim the garment’s fibers for use in new textiles?

More likely, if you can’t repair the garment yourself, or decide that the nail polish you accidentally spilled on your blouse just isn’t the look for you, the garment meets an early end at the bottom of a landfill where it may not decompose for decades. And while one garment doesn’t seem like a lot—how about one million? One billion? All taking up room somewhere out-of-sight, out-of-mind, until one day it no longer can.

To cope with the difficulties of living in the already-and-not-yet, marketing teams have looked to rising consumer dissatisfaction with the status quo and have come up with a solution: More Buzzwords. But what is green technology? What are green initiatives? How does one befriend ecology? What does it mean to be truly sustainable?

We can rest assured that, at the very least, factories are run humanely, workers are paid fairly, textiles are sourced responsibly, supply chains are reducing their carbon footprints, and retailers are committed to stocking their shelves with products from responsible fashion houses and wholesalers. And as fashion enters a metaversal epoch, even the design practices have become digital—from the initial brainstorming sessions, to draping and prototyping, and even sampling, and in the case of NFTs, delivery—thus reducing waste dramatically. This is what is meant by the term Sustainability. And if it sounds like the first-step in a longer journey—it is. And that’s okay. We have to start somewhere.

The cost of doing business

Rebecca Luke has been many things over the years, from costume designer to stylist to educator, and more recently, fashion activist. Her journey in fashion has taken her through the ins-and-outs of some of the ugliest aspects of our industry. And on the more hopeful side, she and a team of like-minded professionals and industry insiders work diligently to focus on the beauty of being As Sustainable As Possible, working to create the bridge necessary from where we’re at now to where we’d like to see the industry going in the seasons ahead.

As Sustainable As Possible began as the natural evolution of Rebecca’s previous venture, Sustainable Style Foundation (2003), which served to educate people about making ethical and sustainable lifestyle choices. In this new venture, ASAP is a for-profit business whose public-facing activities exist primarily in the form of an online database of excellent educational resources as well as a directory of fashion houses and brands that are committed to being as sustainable as possible. According to Rebecca, from their website:

“In the spirit of ‘transparency’, we debated for months what sort of business we should be. In the end, we decided to be a business vs a non-profit. Sustainability and Ethical Choices should be the norm. A normal way to conduct business. Therefore, we will show how this can be done and also be a trusted company by being clear about how we do business. We are a trusted resource because have the experience and we have shared on the site how we go about rating and evaluating [sic]. Think of us like any fashion magazine that features its editors' fav products. We have the same model. We are experts in the area of sustainability and design, and we are helping you vet choices so you can live a lifestyle that will change the world.”

But more than a magazine, ASAP has gone further still by partnering with fashion professionals to provide a rating system to help guide consumers and producers alike, along with their trademarked ASAP T3 Program aimed at working professionals as they strive to move their businesses in a more sustainable direction. According to their website, the T3 Program represents the “three pillars of sustainability: Economic, Environmental & Social.”

ASAP’s guiding philosophy is simple. In Rebecca’s words, “Good design is intrinsically sustainable.” In other words, begin with the end in mind from first principles. But what about businesses that are heavily entrenched in old standards and practices? What if the costs incurred with rebuilding a business from the ground up lead to insolvency?

ASAP provides a certification called a Total Awareness Tag that begins with brand transparency and helps consumers gain awareness and recognition toward a more sustainable business model. A business would, in theory, pledge to make measurable strides toward a specific sustainability goal, and as a check against stagnation, ASAP would require them to reapply annually in order to maintain their Tagged-status. Good for the business, good for the consumer, good for the planet. And good for small businesses and solopreneurs that would not directly benefit from the legal ramifications of restructuring their business models to become a certified B Corp.

But the journey toward a more sustainable future is filled with multiple winding paths. In addition to independent governing bodies, legal distinctions, business structures, award ceremonies, etcetera et al.—there are those whose incredible combination of knowledge, skill, experience, and sheer force of will are forging new paths toward the intersection of commerce and sustainability. These are the new generation of pioneers whose digital-first, direct-to-consumer business models have rewritten the playbook for successful fashion business moving forward. Two such case studies show us that luxury can be both exquisite and sustainable with the right combination of ingredients.

Left: Paychi Guh Lace Pattern Cardigan in Premium Cashmere; Sskein T-Neck bodysuit in baby alpaca. Right: SSKEIN SHAWL NECK LONG BABY ALPACA CARDIGAN.

Home Field Advantage

As we’ve covered before, Sskein is a luxury lifestyle brand based in Seattle, designed in Bellevue, sourced in Peru, hand-packaged in Seattle with biodegradable materials from EcoEnclose, and delivered via Sendle’s carbon-neutral shipping service. Sskein operates on a presale business model with the expressed intention of producing only what customers will actually buy, and working closely with manufacturers to create every efficiency possible in the development and sampling process. The result is sustainably produced small-batch alpaca garments that are as comfortable as they are practical for everyday wear, and that create as little waste as possible.

Paychi Guh takes a similar route by way of Inner Mongolian cashmere, offering a luxury brand that provides all the benefits one would expect from this excellent source textile, whilst working with goat herders and yarn suppliers to ensure the ethical treatment of both the animals themselves and the lands they live upon. Cashmere goats are generally shorn by hand every spring and produce a natural fiber that is at once biodegradable and will last a lifetime of regular use. And there are several grades to choose from, including baby cashmere, worsted cashmere, and even worsted cashmere/silk blends for an experience that exceeds Paychi Guh’s philosophy of Everyday Indulgence.

Both brands are created and owned by women with combined decades of formal education and experience in the fashion industry. Elisa Yip graduated from FIT in New York and designed knitwear for Nordstrom before creating Sskein in 2020. Karen Guh was educated at the University of British Columbia, Philadelphia College of Textiles and Science, and Central Saint Martins in London, before becoming Design Director at Nordstrom, and finally launching Paychi Guh in 2013. And both women understand the urgency of thinking outside the box to make ripples that might one day become waves of change flowing toward a truly sustainable future in the face of a climate crisis unlike any we’ve experienced in our lifetimes.

Paychi Guh Watercolor Crew Short-sleeve in Worsted Cashmere; SSKEIN SHAWL NECK LONG BABY ALPACA CARDIGAN and Wide Leg Alpaca Silk Trousers.

Sustainable Future

I heard a quote once attributed to Mother Teresa when I was young. Evidently, they weren’t actually her words. But they resonate nonetheless. “Not all of us can do great things. But we can do small things with great love.” This extends even into fashion. While the prospect of redirecting a Titanic-sized—nearly $3 trillion—industry leaves many who enter jaded upon exiting, there are innumerable opportunities to engage with local cottage industries that strive with every business decision to leave this world better than they found it. In the case of fashion, sustainability is possible. We just have to start small whilst dreaming big.