Book Club: One Million Followers (Part 2)

12 min read | Book Club | A.M.

Last week we began our Book Club review of One Million Followers by Brendan Kane, covering key thoughts from Chapter 1 and how they might apply to small fashion businesses. We looked at other larger fashion companies and influencers to address key themes apparent in their AW20 marketing mix. We identified Instagram and Pinterest as two key platforms that contribute to a successful omnichannel presence for anyone looking to grow a following in the fashion industry. We did not look at TikTok, however, as we’ll go over that in a later discussion. We did, however, focus on creating video content for Facebook/Instagram’s platforms as a means of gaining recognition from their algorithms.

In today’s segment we’ll look at Chapter 2 as Brendan describes the relative ease with which the Facebook platform allows him to target specific individuals and demographics. In addition, we’ll share our own thoughts on the importance of having a well defined marketing persona before going any further downstream.

Strap in. It’s going to get interesting.

“in order to scale quickly you will need to find the people who’ll not only share your messages for you but also buy your products.”

A Rose By Any Other Name

Quick clarification from the previous article. We made a clear case for reconsidering your brand's online presence and believe that you may already have the necessary skills to do many of the required tasks yourself. But we didn't make a case for why we think it's important to do so in the first place. Why gain a following anyway? Who really needs one million followers?

Well, you do. And so do we, frankly.

This might sound harsh, but the truth is straightforward. It's crazy hard to start and sustain a business, especially in 2020, and especially when you don't have a formal business background. It's even harder when your business model requires that you spend all of your available time performing fashion tasks like designing, sketching, pattern making, draping, prototyping, sourcing, tailoring—emailing manufacturers only to have to call back in their preferred time zones—etcetera ad infinitum.

But the benefits of a well established online presence go beyond connecting with our audiences—it may be the very signifier that attracts much needed capital investment. Brendan writes:

“. . . social media numbers aren’t just desirable for individuals—they apply to brands as well. According to a Wharton business school study, social media popularity can demonstrate a start-up’s ability to build its brand, integrate consumer feedback, and attract specific customer groups. Therefore, some investors take it into account when deciding what they will invest in.” (pg. 21, Kindle Edition)

We may touch on this in another article, but the economics of a small-batch fashion business are dire, with razor-thin margins even under excellent conditions. Most graduate-level fashion designers have all the knowledge they need to implement a fashion line end-to-end, but the most important thing they often lack is money.

Despite the many articles out there promoting advice to the contrary, including pre-sales (paywall) which we certainly recommend in some cases, the truth is that a typical fashion line is expensive and the barrier to entry is high, requiring at least $100k in capital before you can move the needle—much of which you’ll need upfront, and a significant portion of which must go into your marketing campaigns.

The good news is that much of this cost can be amortized. But if you don't have the money upfront, and you can't raise it, and you can't amortize, and you still want to start a fashion line, then you'll be doing all the jobs that would normally go to your employees all by yourself. It's possible, but takes the kind of acumen and grit that typically only dyed-in-the-wool entrepreneurs possess.

Fashion professionals are artists and architects at heart, and that's one of the most amazing things about us. Fashion inspires more than just how we dress; it adds to the very form and pressure of life itself its verve and meaning. But just like you can't create products out of nothing, you can't expect to sell them in today's digital marketplaces without budgeting for an incredibly precise marketing campaign.

Our primary focus, as it correlates with Brendan’s book, will be the Facebook/Instagram platform. But a successful marketing campaign may not start there, and it certainly doesn’t end there. But as such, how many posts have you had that regularly break 100 likes? 1,000? 10,000? How many of those impressions convert to sales?

The average conversion rate for a direct marketing ad spend (i.e. social media) is about 1%. Not a typo. That means only one percent of all digital impressions will likely convert to a sale, on average. As Seth Godin puts it, 3% would be a “homerun.” But some of the latest data indicates that direct marketing gets between 1% - 2% overall, while social media gets just 1% on average.

Additionally, Brendan clearly states in Chapter 1 that in his experience, Facebook's algorithms only reach on average between 2% - 5% of his overall audiences, even after reaching one million followers. That's one-percent of two-to-five-percent of your overall audience that's likely to buy something from you, on average.

In other words, on the Facebook platform, out of 1,000,000 people that follow you, only about 20,000 - 50,000 will ever see what you post, and of them, only about 200 - 500 will buy something from you, on average.

If you're a small-batch fashion business that produces between 5 - 10 SKUs with about as much quantity-per-SKU, and you only have 800 online followers, then learning how to game the social media algorithms to get as many eyes on your products as possible can only stand benefit your business.

We know, math. Ugh.

But the point here is simple. The days of brick-and-mortar dominance are long over. The time for a small-batch revolution is here. And these tools are our lifeline to our audiences in a cacophonic ocean of industry titans and established businesses competing for the very same attention that can either ensure we reach our destination together, or sink our battleships entirely.

Persona Non Grata

In One Million Followers, Chapter 2 is dedicated to targeting audiences, which is generally one of the more basic things you learn in a Marketing 101 course. What’s more interesting here is how this knowledge is successfully applied to social platforms at scale within the last handful of years. But in the interests of our audience, we’ll cover some of the basics in more detail.

Brendan offers several brief yet insightful anecdotes, including the following:

“Let’s say you’re selling women’s yoga pants. It wouldn’t make sense to target men since they aren’t the ones who will need or use the product. . . .Or imagine that you live in a town where everyone is vegan. You wouldn’t open a steak house there. Your business wouldn’t survive.” (pg. 47, Kindle Edition)

Successfully targeting an online audience is directly correlated with successfully identifying a marketing persona. In other words, whatever muse you use as the basis for your fashion business, is precisely the persona you need to start with as you plan your next advertising campaign. Who do you design for? Who buys your garments? Who do you want to buy your garments?

Let’s start with what doesn’t work.

Here’s something we hear all the time: “I make clothes for everyone,” and, “I want to dress the entire Northwest,” and, “I think everyone can use a good pair of fill-in-the-blank,” and, “I just think more people need to learn about the quality of the materials and the time it takes to make their clothing,” etcetera.

The truth is that consumers generally don’t care about textiles and they probably never will. And that’s okay. It’s not the consumer’s job to make clothes, and consumers aren’t directly responsible for the industry that supports their purchasing decisions. One can easily argue that we vote with our checkbooks, and rightly so. But at the end of the day, it’s our responsibility to provide the world with better options so that consumers—who are going to buy something anyway—will be delighted to support a new industry that actually makes the world a better place.

We all go to the dentist, but when’s the last time we sat through a lecture about the nature of anesthesiology? We just want to get the shot over with so we can go about our business. It’s like Seth Godin says time and again: “Make things better by making better things.” Markets will respond accordingly.

Consumers care about identifying problems and solving them. People generally don’t buy a sweater simply because it’s made from Mongolian cashmere; they buy a sweater because they’re cold, and they choose Mongolian cashmere because it aligns with their worldview. And if given the choice between two products of equal or similar quality, consumers will almost always choose the one that’s cheaper, regardless of textiles, construction techniques, or how many hours went into making it, and will deviate from this pattern only when it confirms their biases and lifestyle preferences.

A bit of a tangent, but in this study comparing consumer perception of organic and conventional produce, researchers aggregate data and propose a compelling insight into buyer behavior. As it turns out, people buy a lot of organic produce, not because they know anything about where it comes from, and not because there’s a clear definition of what “organic” really means. People buy organic produce because they fear a long, debilitating march toward their inevitable death and believe that organic produce will give them a healthier quality of life in the interim. In other words, the problem isn't food; the problem is death and the fear associated with it. The solution is identifying how to gain a better quality of life, and consumer perception is that organic food will give them that.

Apple computers are great, but if you can find a PC that has that one killer feature you need, and it’s less expensive than the Apple equivalent, then you’re more likely to buy that PC unless you’re already deeply dependent on Apple’s ecosystem of phones, watches, software, etcetera. People that value the Apple experience will gladly pay a premium to maintain their Apple lifestyle.

Additionally, audiences are more fragmented than ever, requiring better methods for reaching them. Kevin Kelly famously predicted this back in 2008, and the pandemic has only increased the utility of emerging digital marketing methods. As a result, Facebook’s tools are specifically designed for granularity. In One Million Followers, Brendan writes:

“There’s a lot of competition—with a myriad of products, messages, and content, people have an incredible number of options. Consumers and fans have become much more specific in their interests, and there’s a plethora of niche audiences. Use this fact to your advantage.” (pg. 48, Kindle Edition)

But where to start?

A Better Persona

By definition, a marketing persona is intended to represent a larger segment of your target audience, and there are certainly more advanced topics to be explored. However, as we’re following Brendan’s advice, we’ll look at how narrowing your focus and identifying individual consumers can greatly benefit your targeting, especially within our small-batch fashion framework.

In his MasterClass (paywall), Marc Jacobs illustrates this well in Lesson 5. When asked for whom he designs his collections, the answer is a bit cryptic:

“I don’t always have an idea of who I’m designing for. And I remember when I was a student at Parsons, teachers used to say, ‘Who is this woman you’re designing for? Who is she?’ And it used to drive me crazy, because I always say she’s a fashion customer. That’s who I’m designing for. I’m designing for someone who loves fashion. And I know that’s a very vague answer, but I kind of feel like that’s really who it is. . . . I wouldn’t say that myself or anybody on my team, that we sit down with a demographic. . . . Ask any designer who they design for and they say, ‘My woman is young, modern, and sexy.’ But that could mean a million different things to a million different people.”

When we look at Marc’s work over the years, we can clearly see that he has indeed perfectly identified his target customer, but the description is somewhat incomplete. We might say that his psychographic includes anyone that loves fashion, but it also includes people who might identify as innovators at the cutting edge of culture, creative rebels, nonconformists, and even outcasts at the fringes of society—things that resonate strongly with the arts community. That’s because Marc is an artist that creates for the purity of his art, even if he doesn’t always see it that way. And the community that he’s cultivated over the decades resonates with his way of seeing the world. In that sense, Marc actually designs for people like himself—fellow artists and those that love creativity, who perhaps see themselves as creative rebels, and who use fashion as their vehicle for artistic expression.

Some of the most successful entrepreneurs identified and solved their own problems first, then took their solutions to the marketplace. Likewise, some of the most successful designers created lines they themselves wanted to wear because they couldn’t find anything like it in the market already. If you don’t know whom you’re designing for, take a look in the mirror. There’s a chance your target customer is looking right back at you.

So before you can plan a direct marketing campaign, you have to be crystal clear on whom you want to target and why. And before you can identify a target audience, you have to be clear on whom you’re really making apparel and accessories for to begin with.

Now that's out of the way, let's have a look at what can work for us.

The Red Pill

Hard truth: This is one of the least classically artistic parts of the process, but Brendan does a wonderful job of getting right to the point, offering an excellent checklist that can get the ball rolling. The steps, in order, require that you identify the following:

Gender and Age of your target audience;

Your specific marketing Goals;

Audience Location;

Their specific Interests;

Their specific Lifestyle traits;

Your brand’s leading Competitors operating in the same space.

Brendan lays out a handful of iterations on this theme including, “Age 18-35 that likes Lululemon; Age 36-50 that likes Lululemon,” you get the idea.

Eventually you’ll identify the person or people you believe will be the right fit, which might look something like this: Female, age 35-55, under 6 feet tall, wears dress size 6-12, lives in Bellevue, works at Microsoft, earns $100k/year, reads Vogue, prefers blazers and pants over dresses, visits Seattle Art Museum twice a month, loves winter but hates cold weather, says they love coffee but secretly can’t stand the smell—and so on until you’ve really honed in on whom you want to present your message, and who is most likely to receive it.

Again, this is meant to be a real person out in the real world, and as such, your persona will greatly benefit from your actual interactions with your actual customers. Knowing them well is the key to serving them well and delighting them with your brand messaging. And it’s a key to using the Facebook algorithm to your advantage.

Hubspot have a rather delightful online persona generator that allows you to create a basic persona that can help you further your progress if you get stuck.

If you don’t have a following of any kind, especially if you’re just starting out, Brendan offers insight into how you can begin identifying a potential community you can serve by referencing SVP of Growth at FabFitFun, David Oh:

“If you think your consumer base consists of women between eighteen and thirty years old, go out and speak to people in that demographic. See how they feel about your message, ideas, and content. Use your friends, family, and acquaintances as resources to help you do market research.” (p. 52, Kindle Edition)

The best part, it’s probably free—especially the speak-with-your-family bit—and simply requires that you hang out with cool people that are likely to give you honest feedback about what you’re trying to bring into the world. And that feedback will be another key to succeeding which we’ll cover in a later article.

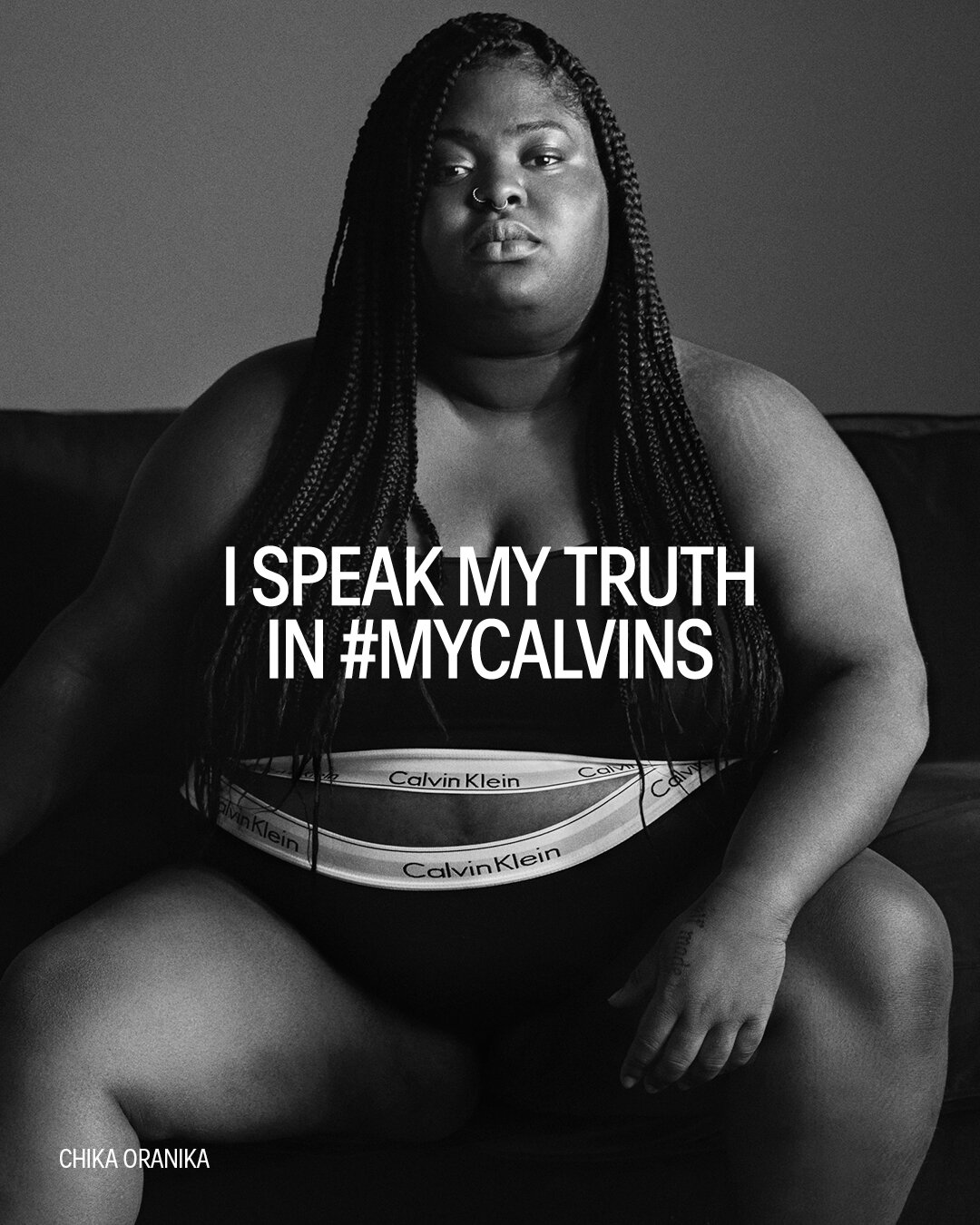

Once you’ve identified whom the campaign will target, you’re ready to begin your campaign—almost. You know whom you’re trying to reach, but what are you going to say? How will you say it? It’s time to plan out your message and produce your campaign materials—still images, video, copy, graphic design—which is one of the most creative aspects of the entire process, and one we all tend to gloss over in our haste.

Up Next

Nailing down the correct tone for your message can make the difference between a message well received and falling upon deaf ears, or worse. And as you may have already guessed, we’ll cover this in more detail in the next article. So join us next week as we survey some of the year’s top fashion advertisements and design a campaign message for a fictitious brand with achievable results in mind.

In today’s segment we’ll look at Chapter 2 as Brendan describes the relative ease with which the Facebook platform allows him to target specific individuals and demographics. In addition, we’ll share our own thoughts on the importance of having a well defined marketing persona before going any further downstream.